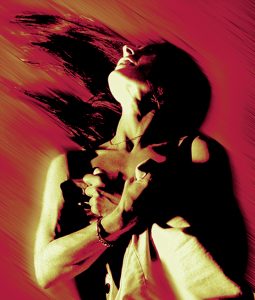

Performer Jackie Wilford experiences paradise teaching flamenco in the Seychelles

This article, first published in the Winter 2010 edition of Animated, is reproduced by permission of Foundation for Community Dance. All Rights Reserved. See www.communitydance.org.uk/animated for more information.

Teaching children how to dance on a tropical island with a deep culture of music and rhythm isn’t the worst job in the world. Publicity for the Seychelles speaks about ‘Paradise, 1000 miles from anywhere,’ and it’s no lie. Think coral and granite islands in turquoise seas, palm trees and rainforests. Here there is no debilitating junk food, and entertainment is more about participation than consumption. What did young people in such an environment need from outsiders? It’s true that the guitarist Chris Mullett, my co-founder at Flamenco Express, and I have performed and taught all over Britain and Europe since 1996. But what could he and I teach these young people about rhythm that they didn’t already know? Shouldn’t they by rights be teaching us ? And, specifically, what did flamenco have to offer them anyway?

Nevertheless our job during three separate trips in 2006, 2007 and 2008 was to teach flamenco workshops at the International School Seychelles. The total number of students in each of our groups was about 20, ranging in age from 6 to 18. We also had to produce a televised performance at the end of each week-long visit. This wouldn’t be an easy task in the UK, let alone in a place where few of the children have ever seen flamenco and many speak only French or Creole. And the only shoes they wear are flip-flops or trainers. (Leather doesn’t last long in the rainforest.) But rhythm is a universal language, and Seychellois have a lively culture. Music and dance is an integral part of people’s lives. The music heard on the streets, in the markets and at parties is similar to Jamaican reggae, but based on the same rhythm as tanguillos, which is a flamenco compass (or, again, rhythm). Seychelles is a culture so steeped in rhythm that wherever there’s a

group of people someone will have a drum or sound system, and there will be dancing whether the music plays or not.

On the main island, Mahe, dancers and drummers arrive on the beach on Wednesday nights. The drumskins are tuned by the driftwood bonfires, and inside a pulsating circle the dancing goes on into the night. Dance has always been taught in all of the schools, and a country with a population of only 40,000 has a national dance academy. In addition the African, Asian and European cultural heritage has produced a range of local dance forms – in particular the moutia, sega, and contre-dance – which are still alive. Moutia is possibly the most widespread; it combines rhythm and song, as does flamenco.

But I didn’t know any of this when we first arrived. If I had I would’ve been less apprehensive about teaching flamenco in the middle of the Indian Ocean. The fact that the classes were over-subscribed two weeks before we left London was not a help.

Our days started early, and by noon we’d already done two 90-minute workshops. The children were always enthusiastic and eager to learn. Because of a healthy diet they’re fit and slender, and their stamina and concentration is truly amazing.

Every year each group we worked with consisted of equal numbers of boys and girls, and each year studied different rhythms, or compas. They tackled tangos, farruca, fandangos, and guijarras, which are various flamenco rhythms, dances and songs. Using palmas (hand clapping), picas (finger clicking) and footwork they worked on complex co-ordinations and rhythmic patterns. Wearing whatever kind of heeled shoes they could get hold of, they devised their own choreography and chose their own steps. At the end of each week they always produced enough material for the half-hour performance. It was a real challenge for them, but they relished it and sweated to be as good as they could be. On the night itself they were pure magic, the boys in their brightest shirts and the girls with the roadside frangipani in their hair. They always made me cry.

Some children stand out in my memory. Harry was a newcomer to Seychelles, big for his age and slightly defensive in his strange surroundings. He seemed to be a natural choice for dance captain and rhythm leader, and this role turned him from an awkward, spiky boy into a real helper who fitted in and merited respect. Alec was very concerned with perfecting the choreography, as he was convinced it would improve his skateboard technique. Jane already wanted to be an actor, and was an exemplary dance captain. She had advanced musical skills, played the drums and found that flamenco gave her new ideas. And then there was Ryan, the only student who had real problems with concentration and being still. By the end of the week he seemed to have found, in rhythm, a framework that enabled him to focus on tasks and retain instruction while also allowing him to express his creativity. He excelled at inventing patterns and teaching them to the rest of the class, and received respect in return. On the night of the performance he shone. The combination of the natural human response to rhythm, plus a sympathetic environment, had allowed him to discover skills and rewards he hadn’t known before.

It was noticeable that children gained status from being willing to help each other, and they took pleasure in doing so. Their determination can be summed up by the worried nine-year old girl who came to me at the start of the second day – after only one class of flamenco – and apologised, ‘Please. Miss Jackie, I can’t remember all of yesterday’s choreography.’ Or the two six year-olds who, when asked to be at the studio at four o’clock for final rehearsal, came to me and said, ‘We don’t know time.’ They were old enough to learn choreography but not to tell the time. Naturally their classmates ensured that they arrived at four.

Vital to the success of the entire project was the Seychelles ingredient of co-operation between the students. In the studio the children would help each other with steps, and some as young as six would translate my instructions into French or Creole for their fellow students. Others videotaped, lit and staged the show alongside a wide range of other jobs. Most striking of all was the level of unofficial, everyday and systemic help they offered for no apparent reward other than the joy of performing, respect among their peers and the satisfaction of what, from the evidence of this experience, is the natural human instinct to communicate with and assist each other. The apparent side effects of this cultural solution to the historic problems of living together are openness, confidence and a genuine interest in other people, in what they have to say and in who they are. This is a society that likes people, and especially people who like sharing. As artists and teachers we were there to share. This meant that we were also liked, or at least granted respect. We found we didn’t have to prove our point or assert our authority, which isn’t always the case in cultures that are more focused on winning and individual excellence. This openness allowed the students to enjoy flamenco and master new dance skills in a week. Their respect also extended to the art form itself, which is an essential first step and something they seemed to grasp instinctively.

Flamenco offered them another medium for their innate creativity. But they were obviously capable of taking immense joy from almost any activity, especially those involving the group. As for us, I feel we learned as much as we taught. Even spread across three years the entire experience was, and still is, hugely inspiring.